Urinary Proteomics

Overview of Urinary Proteomics and Its Importance in Biomedical Research

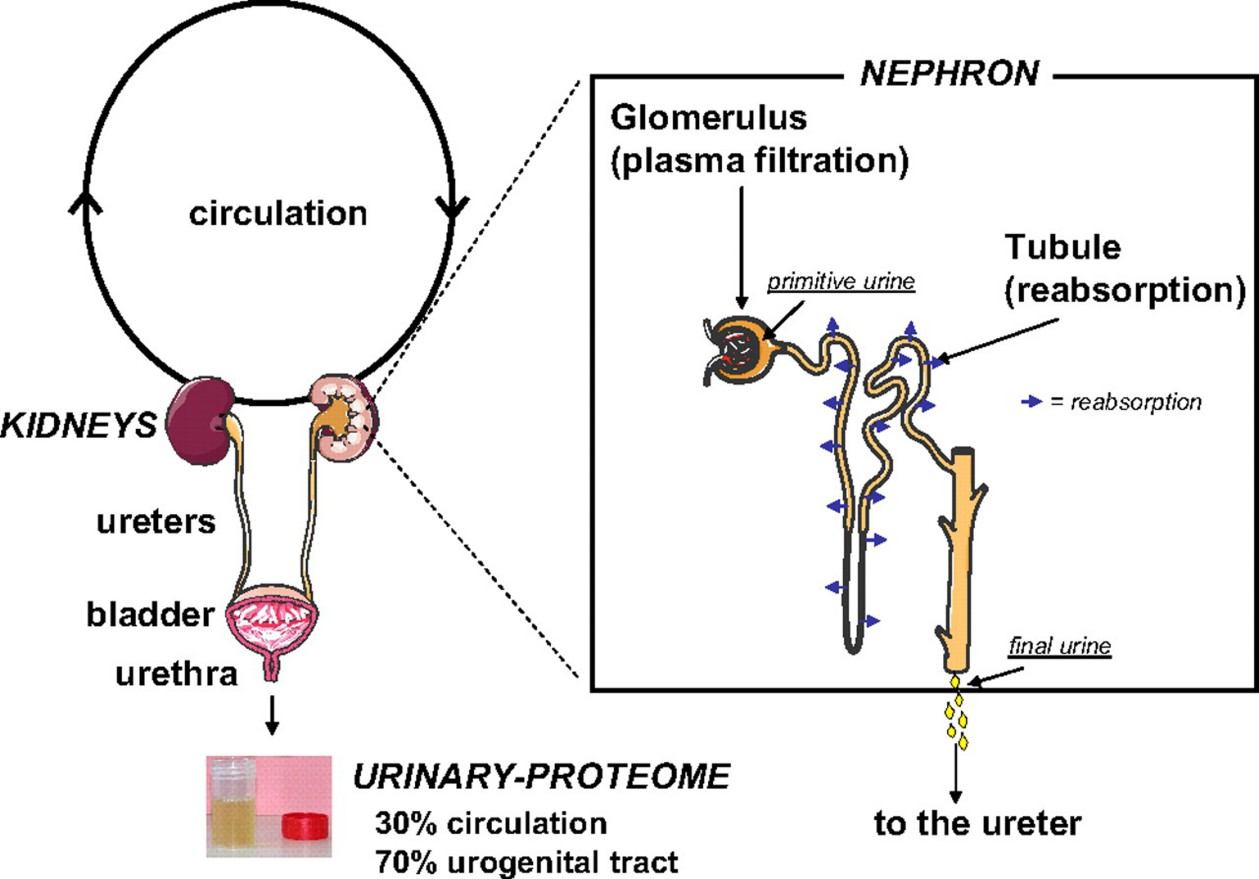

Urinary proteomics has emerged as a powerful analytical discipline for the discovery of non-invasive biomarkers. Urine contains a diverse proteome that reflects physiological and pathological processes across multiple organ systems. The urinary proteome captures signals from the kidney, urogenital tract, cardiovascular system, and immune system. Its composition also mirrors systemic metabolic and proteostatic changes.

Modern mass spectrometry enables high-depth and high-throughput analysis of urinary proteins. These advances facilitate early disease detection, mechanism-based classification, and pharmacodynamic evaluation. Urinary proteomics now supports precision medicine, translational research, and development programs. The field continues to expand as analytical sensitivity and data fidelity improve.

Figure 1. Circulation process of urine in the kidney (Decramer S, et al., 2008).

Why Urine is an Ideal Sample for Proteomics Research?

Urine offers several advantages as a research matrix. The collection process is simple and non-invasive. This reduces patient burden and increases sample compliance in large-scale studies. Urine contains fewer high-abundance proteins than plasma. This improves the detection of low-abundance biomarkers. The matrix also exhibits high stability because it lacks proteases that are abundant in blood.

Urine reflects dynamic physiological changes because it comes into direct contact with renal and urogenital tissues. Many diseases alter glomerular filtration, tubular reabsorption, or immune activity. These changes produce measurable proteomic signatures. As a result, urine is well-suited for longitudinal monitoring, early screening, and evaluation of therapeutic response.

Advanced Quantitative Proteomics Platforms for High-Depth Urinary Analysis

Data-Independent Acquisition (DIA)

DIA collects fragment-ion data for all precursor ions systematically. This eliminates stochastic precursor selection and improves quantification stability. DIA resolves complex urine matrices with high confidence. The method supports biomarker discovery, pathway profiling, and differential proteome analysis across large cohorts.

DIA libraries derived from deep urinary datasets enable sensitive peptide identification. They also facilitate standardisation across instruments and laboratories.

4D-DIA and dia-PASEF

4D-DIA and dia-PASEF incorporate trapped ion mobility spectrometry. This separates peptides based on mobility, mass, retention time, and fragmentation behaviour. The four-dimensional dataset improves analytical resolution and reduces interference.

The increased sequencing speed benefits discovery-driven projects. The higher sensitivity enables the detection of ultra-low-abundance urinary proteins related to inflammation, fibrosis, or metabolic dysfunction.

Targeted Proteomics and PRM-PASEF

Targeted proteomics offers high-accuracy quantification for predefined biomarker panels. Parallel Reaction Monitoring (PRM) combined with PASEF enhances selectivity. The method provides absolute quantification when paired with stable isotope–labelled standards.

PRM-PASEF delivers robust quantification for signalling molecules, transport proteins, renal injury markers, and pharmacodynamic biomarkers.

Our Comprehensive Urinary Proteomics Workflow at Creative Proteomics

- Project design: We define analytical objectives, target pathways, and sample numbers.

- Sample processing: Proteins undergo desalting, concentration, and enzymatic digestion.

- Mass spectrometry acquisition: We apply DIA, 4D-DIA, dia-PASEF, and PRM-PASEF depending on study goals.

- Data analysis: Our bioinformatics team performs peptide identification, quantitative normalization, pathway mapping, and biomarker scoring.

- Reporting: Clients receive a detailed scientific report with analytical parameters, statistical outputs, biological interpretation, and study recommendations.

Applications of Urinary Proteomics

- Kidney diseases: Detection of glomerular injury, tubular dysfunction, and fibrotic progression.

- Metabolic disorders: Profiling of diabetic nephropathy, obesity-related inflammation, and metabolic syndrome.

- Oncology: Identification of tumor-derived proteins for bladder cancer, prostate cancer, and renal carcinoma.

- Cardiovascular disease: Monitoring of endothelial dysfunction and oxidative stress markers.

- Neurological disorders: Assessment of neuroinflammatory and neurodegenerative processes reflected in urinary proteins.

- Drug development: Evaluation of pharmacodynamic biomarkers, toxicity indicators, and target engagement.

Why Choose Creative Proteomics for Urinary Proteomics Projects?

- Deep scientific expertise built on practical experience: Creative Proteomics brings more than two decades of experience in proteomics and mass spectrometry. Our scientists understand how biological variability in urine affects the detection and quantification of proteins.

- Advanced technologies optimized for urine samples: We apply state-of-the-art quantitative platforms, including DIA, 4D-DIA, and targeted PRM. These methods provide stable quantification across large sample sets, enabling the detection of low-abundance proteins that are often critical for disease-related pathways.

- Strong focus on data quality and biological interpretation: We implement strict quality control at each analytical step and provide transparent reporting. Our bioinformatics analysis emphasizes pathway-level interpretation rather than isolated protein lists.

- Seamless transition from discovery to targeted validation: We guide projects from broad discovery studies to targeted validation using absolute quantification. This continuity minimizes technical variation and improves confidence in biomarker selection.

- Collaborative communication and project support: We work closely with our clients throughout the project lifecycle. Our scientists provide clear guidance on experimental design, sample preparation, and data interpretation.

Sample Requirements for Urinary Analysis

| Parameter | Requirement |

| Sample Type | Human or animal urine |

| Minimum Volume | 5–10 mL (standard); ≥50 mL recommended for exosome enrichment |

| Collection Method | Midstream urine; first-morning sample preferred |

| Container | Sterile polypropylene tube |

| Processing | Centrifugation at 2,000 × g for 10 min to remove debris |

| Storage | −80°C; avoid repeated freeze–thaw cycles |

Note:

We recommend first-morning midstream urine due to higher protein concentration. Samples require immediate cooling. Centrifugation removes cellular debris and particulate matter. Filtration and protease inhibitors further stabilize protein composition.

Consistent storage below −80 °C preserves protein integrity for long-term biobanking. Quality control metrics ensure batch uniformity and minimize analytical bias.

FAQ

-

Q1: Why is urine considered less complex than serum or plasma for proteomics?

A1: Urine is considered less complex than serum or plasma due to its lower overall protein concentration and reduced presence of high-abundance proteins such as albumin and immunoglobulins. This reduction in complexity enables the mass spectrometric interrogation of lower-abundance proteins with improved depth and quantitative precision.

-

Q2: How is data from urinary proteomics interpreted?

A2: Data analysis includes peptide identification, quantitative normalization, differential protein analysis, pathway enrichment, and statistical modeling. Advanced bioinformatics, including machine learning, can identify patterns and predict functional relationships between proteins and disease mechanisms.

-

Q3: How does DIA improve reproducibility compared to traditional shotgun proteomics?

A3: DIA systematically fragments all detectable precursor ions, unlike DDA, which selects ions stochastically. This ensures consistent peptide coverage across samples, enabling high reproducibility and reliable quantification in large-scale studies.

-

Q4: How do extracellular vesicles (EVs) improve urinary biomarker detection?

A4: EVs carry proteins, RNA, and lipids from their cells of origin, including diseased tissues. Isolation of urine EVs concentrates these molecules, increasing the likelihood of detecting low-abundance biomarkers.

-

Q5: What is the current detection depth achievable in urinary proteomics?

A5: With modern high-resolution MS, researchers have identified several thousand proteins in normal human urine. For example, deep profiling using advanced separation strategies has identified over 6,000 unique urinary proteins in healthy individuals. This depth supports broad biological insight and increases the likelihood of capturing disease-relevant biomarkers.

Demo

Demo: Urine Proteomics for Detection of Potential Biomarkers for End-Stage Renal Disease

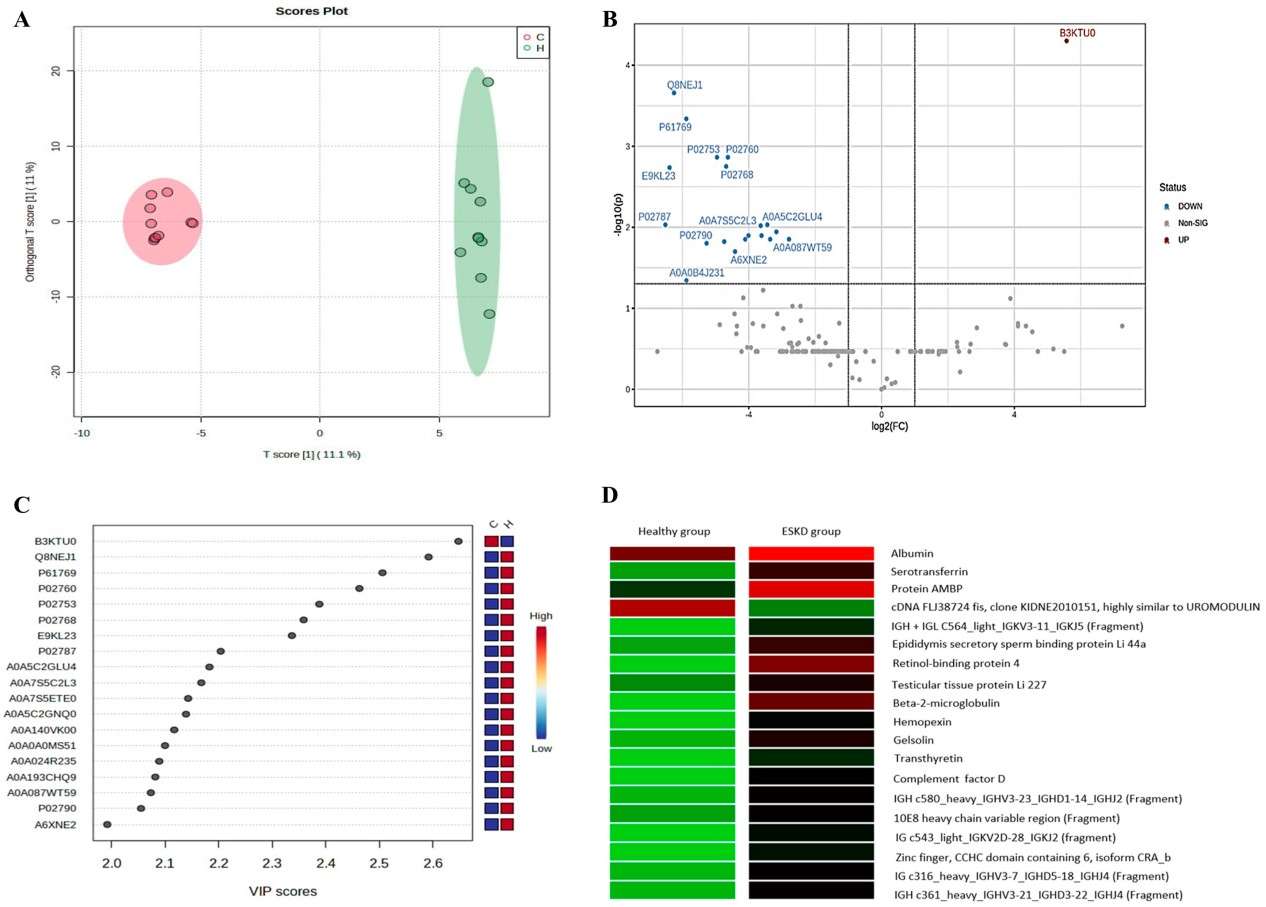

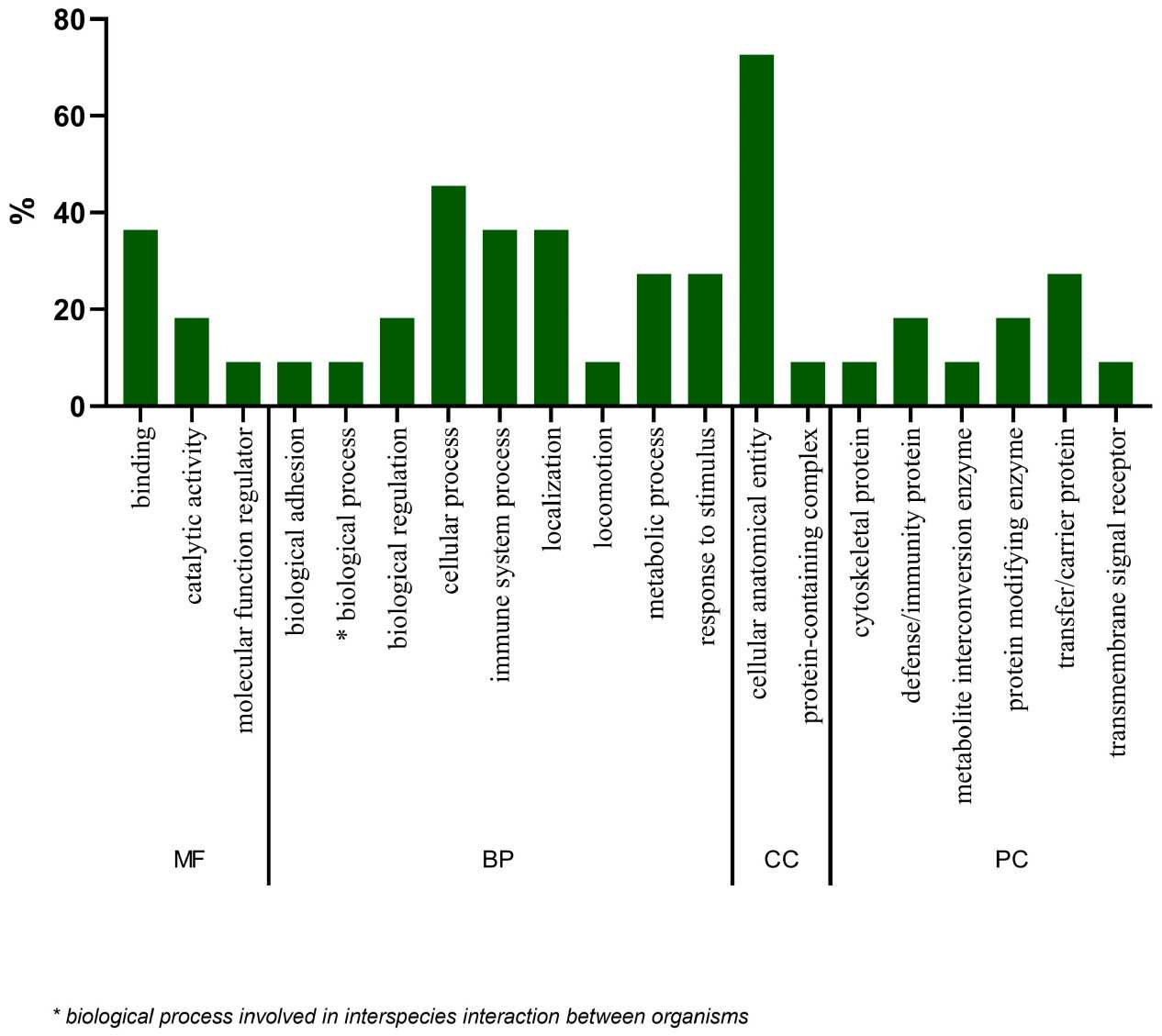

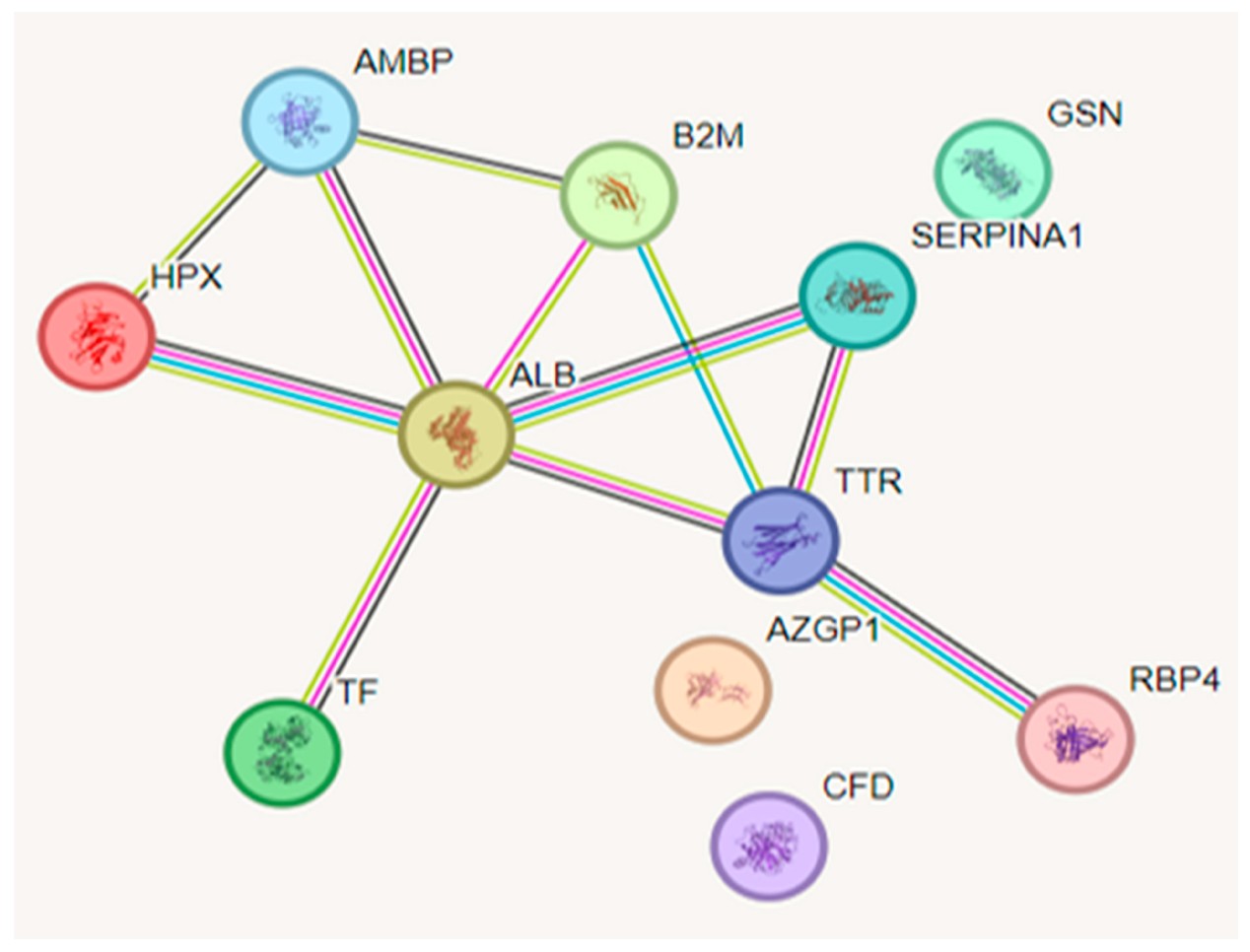

This study compared urinary proteomes of healthy individuals and chronic kidney disease patients using LC–MS/MS. It identified distinct protein expression differences, including elevated beta‑2‑microglobulin levels in CKD patients, which correlated negatively with renal function. These findings support urinary proteomics as a non-invasive approach for detecting and monitoring progression toward end-stage renal disease.

Figure 2. Quantitative characterization of the urinary proteomic profile of the control and hemodialysis groups (Silva N R, et al., 2025).

Figure 3. Gene ontology (GO) analysis of the 19 statistically significant proteins (Silva N R, et al., 2025).

Figure 4. Functional interactions between proteins (Silva N R, et al., 2025).

-

Case Study

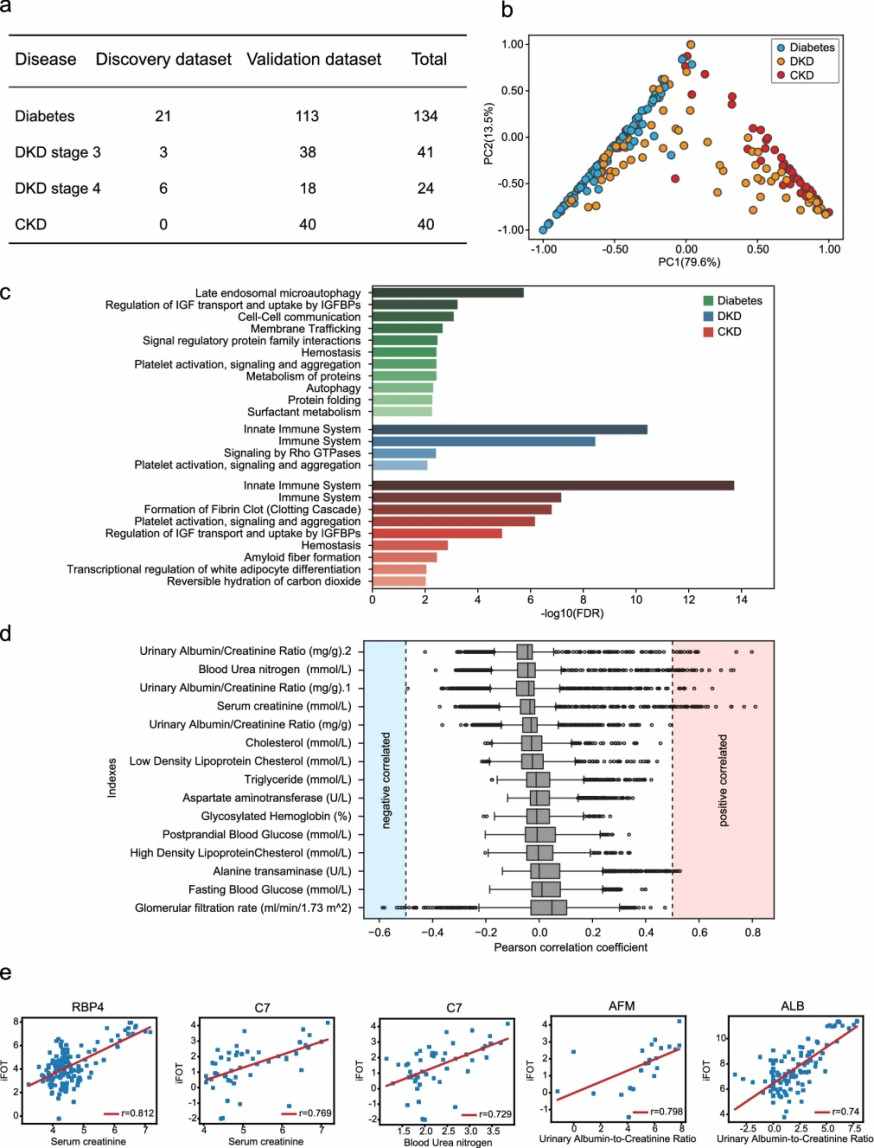

Case: Urine proteomics identifies biomarkers for diabetic kidney disease at different stages

Background:

Type 2 diabetic kidney disease (DKD) is a leading cause of chronic kidney disease (CKD) and end-stage renal disease (ESRD). Current diagnosis relies on invasive kidney biopsy or clinical measures (eGFR, albuminuria), which are limited in accuracy and early detection. Noninvasive biomarkers for early detection and monitoring of DKD are needed.

Purpose:

To establish a urinary proteomics workflow to identify protein biomarkers that can differentiate DKD from uncomplicated diabetes, distinguish DKD stages, and monitor early disease progression.

Methods

- Cross-sectional study with 252 urine samples from patients with diabetes without nephropathy, DKD (stages 3 and 4), and CKD without diabetes.

- Proteins were extracted from urine pellets, digested with trypsin, and analyzed using nano HPLC coupled with LC–MS/MS.

- Label-free quantification (iBAQ/iFOT) and statistical analyses (DEPs identification, PCA, logistic regression, ROC) were performed.

- Classifiers were built to differentiate DKD from diabetes, DKD3 from DKD4, and identify early DKD progression (pre-DKD3).

Results

- 2946 proteins were quantified overall, with a median of 571 proteins per sample.

- A 2-protein classifier (ALB, AFM) distinguished DKD from diabetes (AUC = 0.928).

- A 3-protein classifier (ANXA7, APOD, C9) distinguished DKD3 from DKD4 (AUC = 0.949).

- A 4-protein classifier (SERPINA5, VPS4A, CP, TF) identified early-stage DKD3 from diabetes (AUC = 0.952).

- DEPs were associated with complement cascade, immune response, and metabolic pathways, reflecting disease progression.

- Follow-up of 11 patients confirmed progression in 2 predicted pre-DKD cases.

Figure 5. Urine proteomic analysis of Diabetes, DKD, and CKD.

Conclusion

Urinary proteomics is a non-invasive and reproducible approach for detecting, staging, and monitoring the progression of DKD. The study identified robust biomarker panels and provided insights into molecular pathways underlying DKD, supporting early intervention in high-risk patients.

Related Services

References

- Joshi N, et al. Recent progress in mass spectrometry-based urinary proteomics. Clinical Proteomics, 2024, 21(1): 14.

- Decramer S, et al. Urine in clinical proteomics. Molecular & cellular proteomics, 2008, 7(10): 1850-1862.

- Silva N R, et al. Urine Proteomics for Detection of Potential Biomarkers for End-Stage Renal Disease. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2025, 26(12): 5429.

- Fan G, et al. Urine proteomics identifies biomarkers for diabetic kidney disease at different stages. Clinical proteomics, 2021, 18(1): 32.